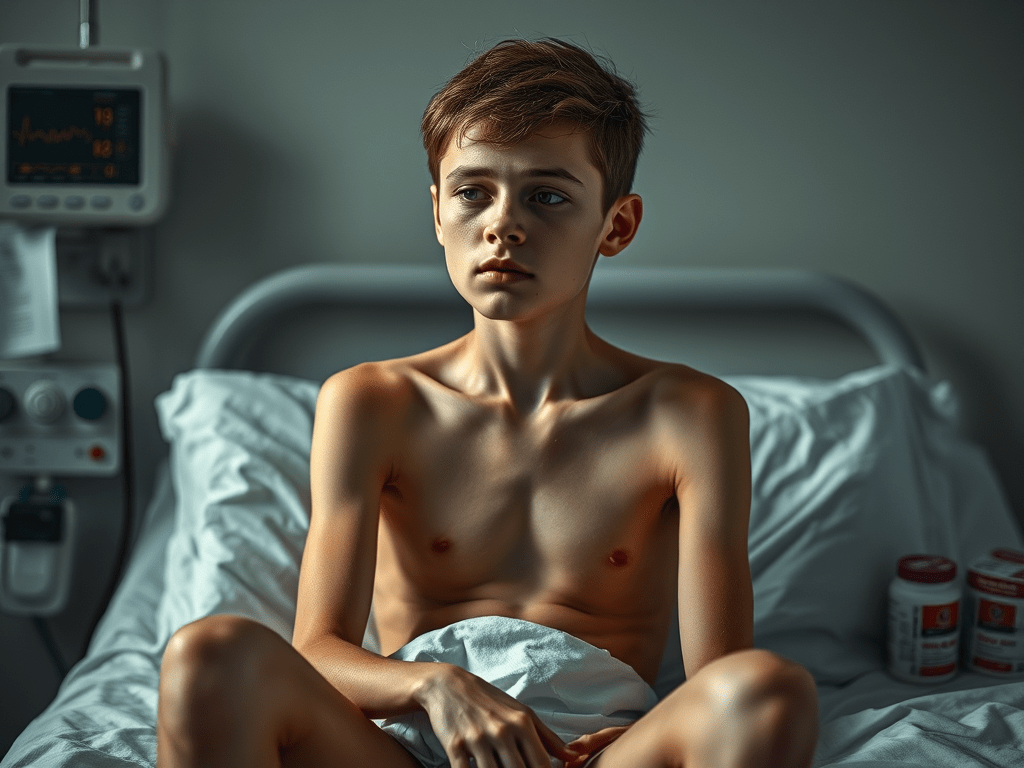

The first time I heard the phrase “anorexia nervosa hospitalization criteria,” I was sitting in my primary care doctor’s office, clutching my jacket around my shivering frame. The room wasn’t cold. My body had just forgotten how to maintain its temperature—one of many systems slowly shutting down after two years of starvation.

“Your heart rate is 42 beats per minute,” she said, looking up from her chart. “Your potassium is dangerously low. You meet anorexia nervosa hospitalization criteria. This isn’t optional anymore.”

I’d spent years bouncing between various eating disorder diagnoses—restricting, then purging, then restricting again in an endless cycle of self-destruction. No one treatment center had the complete answer, but each contributed something to my eventual recovery. This is my story of navigating the complex world of eating disorder treatment, from inpatient programs to outpatient support, medication trials, and the complicated journey toward something resembling recovery.

Anorexia Purging Type: Beyond the Stereotypes

Most people picture anorexia as pure restriction—someone who simply doesn’t eat. The reality is more complicated. My diagnosis of anorexia purging type meant I restricted severely but also engaged in purging behaviors. This combination created a particularly dangerous physical situation that my treatment team constantly reminded me could be fatal.

During my intake at Walden Eating Disorder treatment center, the psychiatrist explained why this combination was so medically precarious.

“Your body is already nutritionally compromised from restriction,” he said. “When you add purging, you’re creating electrolyte imbalances that can cause cardiac arrest with no warning.”

The assessment was frightening but necessary. Throughout my three-month stay at Walden, the medical team monitored my vital signs multiple times daily. Laboratory tests became a regular part of life, checking for the invisible damage happening inside my malnourished body.

What surprised me most about treatment was discovering how many others shared my diagnosis. Media representations of eating disorders tend to focus on either extreme restriction or binging and purging, rarely acknowledging how frequently these behaviors overlap or alternate. In group therapy, I met others with similar patterns who understood the particular shame and physical toll of this diagnosis.

UNLOCK THE ULTIMATE WEIGHT LOSS SECRET!🔥 Tap into your body’s natural fat-burning power with a method celebrities have quietly used for years! 💪

Borderline Personality Disorder Eating Disorder: The Complication No One Discussed

Six months into my recovery journey, a new diagnosis entered the picture: borderline personality disorder. The treatment team explained that borderline personality disorder eating disorder comorbidity is actually quite common, though rarely discussed publicly.

“Your emotional regulation difficulties and identity issues aren’t separate from your eating disorder,” my therapist explained. “They’re intertwined. We need to address both to create lasting recovery.”

This dual diagnosis explained so much about my erratic treatment history. The black-and-white thinking characteristic of BPD had manifested in my all-or-nothing approach to recovery. I was either perfectly following my meal plan or completely abandoning it. The emotional intensity had also fueled cycles of restriction and purging as desperate attempts to manage overwhelming feelings.

Learning about this connection between my personality structure and eating disorder didn’t make recovery easier, but it made it more coherent. For the first time, my behaviors made sense within a larger context, rather than seeming like random self-destruction.

Anorexia and BPD: When Diagnoses Overlap

The relationship between anorexia and BPD created particular challenges in treatment. My fear of abandonment led to intense attachments to certain treatment providers, while my tendency toward splitting caused me to idealize some approaches while devaluing others.

“You’re trying to use food behaviors to manage BPD symptoms,” my psychiatrist observed during a particularly difficult period. “And then BPD emotional swings trigger eating disorder behaviors. We need to interrupt this cycle.”

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) became a crucial component of my treatment plan. Learning skills for emotional regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness provided alternatives to using eating disorder behaviors for emotional management.

The most valuable skill proved to be mindfulness—learning to observe urges to restrict or purge without automatically acting on them. This small space between feeling and action created room for choice, something I hadn’t experienced in years of compulsive behaviors.

Montecatini Eating Disorder Treatment: A Different Approach

After discharge from Walden, I transitioned to a partial hospitalization program at Montecatini Eating Disorder Treatment center in California. The contrast between programs was striking and illuminating.

While Walden had focused heavily on medical stabilization and weight restoration, Montecatini emphasized psychological aspects of recovery. Their approach incorporated more family therapy, trauma work, and exploration of underlying issues driving disordered eating.

The daily schedule included conventional therapy groups but also incorporated movement classes, art therapy, and cooking skills—practical tools for building a life beyond the eating disorder. For someone who had forgotten how to eat normally, cooking groups provided crucial relearning of basic food preparation skills.

Most valuable was their approach to meals. Rather than the hospital-style dining at Walden, Montecatini created a more homelike atmosphere. Staff ate alongside patients, modeling normal eating behaviors and engaging in conversation that wasn’t focused on food.

“The goal isn’t just to feed you,” my primary therapist explained. “It’s to help you relearn that meals are about nourishment, yes, but also connection and even pleasure.”

This normalized approach to food challenged my entrenched belief that eating was a clinical activity requiring measurement, rules, and supervision. Gradually, meals became less terrifying and occasionally even enjoyable.

Zoloft Eating Disorder Treatment: The Medication Component

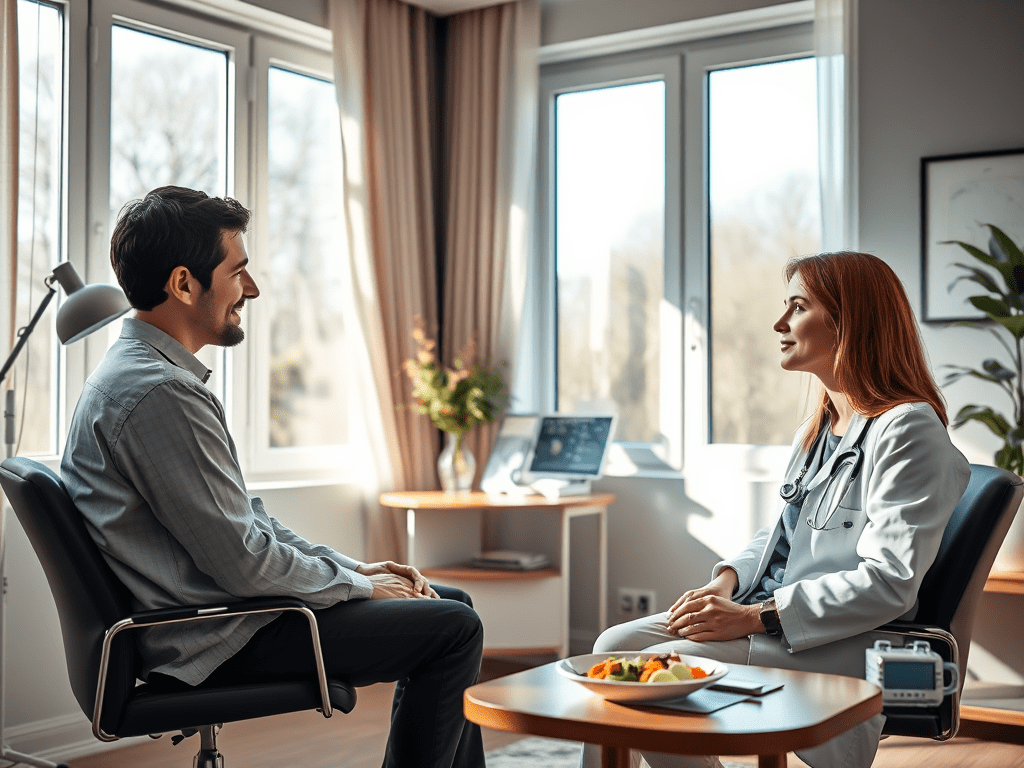

Medication proved to be a controversial but ultimately helpful component of my recovery. When my psychiatrist first suggested Zoloft for eating disorder and comorbid depression symptoms, I was resistant.

“I don’t want to take medication,” I insisted. “I want to recover through willpower and therapy.”

This perspective, my doctor gently explained, reflected eating disorder thinking rather than medical reality.

“Would you tell a diabetic to recover through willpower rather than insulin?” she asked. “Your brain chemistry has been affected by malnutrition and mental illness. Medication can help create a foundation for therapy to work more effectively.”

The decision to try Zoloft wasn’t made lightly. We discussed potential side effects, including initial appetite changes that could be triggering during recovery. Starting at a low dose and gradually increasing helped minimize these effects.

Within six weeks, subtle improvements emerged. The constant background noise of anxious thoughts quieted somewhat. Obsessive food calculations became less automatic and consuming. Most importantly, I became more receptive to therapy, better able to consider perspectives beyond my eating disorder’s rigid viewpoint.

Research on zoloft eating disorder treatment indicates it can be particularly helpful for patients with comorbid depression or anxiety—a finding consistent with my experience. The medication didn’t cure my eating disorder but created psychological space for recovery work to take root.

Naltrexone for Binge Eating Disorder: Addressing Different Symptoms

As my recovery progressed, my symptoms evolved. Periods of restriction gave way to episodes of binge eating—a common but discouraging development in recovery. My psychiatrist suggested naltrexone for binge eating disorder symptoms, explaining its mechanism as an opioid antagonist that can reduce the rewarding aspects of binge foods.

“Naltrexone isn’t appropriate for everyone,” she cautioned. “But for some patients, it helps interrupt the neurochemical rewards that reinforce binge behaviors while you’re learning psychological skills.”

The research on naltrexone remains somewhat limited compared to SSRIs, but combined with my therapy program, it provided modest benefits during a difficult transition period. The medication didn’t eliminate urges entirely but created a slight buffer—enough to implement the skills I was learning rather than acting automatically on urges.

This medication approach reflects the evolving understanding of eating disorders as complex biopsychosocial conditions requiring multifaceted treatment. No single pill, therapy technique, or program provides complete recovery, but each component can contribute to the overall healing process.

Renfrew Virtual IOP: Treatment During a Pandemic

My recovery journey took an unexpected turn when the COVID-19 pandemic forced treatment centers to quickly adapt. After a relapse triggered by pandemic isolation, I enrolled in Renfrew Virtual IOP (Intensive Outpatient Program)—a format I was initially skeptical about.

“How can eating disorder treatment work virtually?” I questioned. “Don’t they need to see me eat?”

Despite my doubts, the program proved surprisingly effective. Daily group therapy sessions via video conference provided structure and connection during an isolating time. Meal support happened virtually, with participants eating on camera together under staff supervision.

The Renfrew Virtual IOP format had unexpected advantages. Practicing recovery skills in my actual living environment, rather than the artificial setting of a treatment center, created more directly applicable learning. When faced with food challenges, I couldn’t rely on staff to prepare meals or remove triggering foods—I had to develop these skills myself with guidance.

The program also eliminated the geographical barriers that had previously limited my treatment options. Living in a rural area, I’d previously needed to relocate for intensive treatment. The virtual format allowed access to specialized care without disrupting my entire life.

This experience highlighted how treatment models continue evolving to meet patient needs. While virtual treatment isn’t appropriate for those requiring medical stabilization, it offers a valuable option for maintaining recovery or addressing emerging symptoms before they require higher levels of care.

Clementine Twin Lakes Reviews: The Importance of Treatment Matching

Throughout my recovery journey, I connected with others at various stages of treatment. Comparing notes about different programs revealed how crucial appropriate treatment matching can be for recovery success.

A fellow patient shared her experience at Clementine Twin Lakes, a residential program specifically for adolescents. The Clementine Twin Lakes reviews she shared emphasized the program’s developmental focus—something she found crucial as a 16-year-old navigating both eating disorder recovery and normal adolescent development.

“Adult programs didn’t address the specific challenges of being a teenager with an eating disorder,” she explained. “Clementine understood how to balance normal developmental needs with recovery work.”

Her experience highlighted the importance of age-appropriate treatment—a factor I hadn’t previously considered. Similarly, programs vary in their appropriateness for different diagnoses, comorbidities, and recovery stages.

When evaluating treatment options, I learned to consider factors beyond just level of care or location:

- Does the program have specific expertise in my particular diagnosis?

- How do they handle psychiatric comorbidities?

- What is their approach to medication?

- Do they incorporate family involvement appropriately?

- What is their treatment philosophy regarding exercise, weight restoration, and nutritional approaches?

No program is universally ideal for all patients. Finding the right match requires honest assessment of individual needs and circumstances, often with guidance from outpatient providers who know your specific situation.

Eating Disorder VA Rating: Navigating Insurance and Coverage

The financial aspect of eating disorder treatment created another layer of complexity in my recovery journey. As a veteran, I explored the eating disorder VA rating system to access coverage for specialized care not available within the VA system.

The process revealed how challenging insurance navigation can be for eating disorder patients. Many insurance companies limit coverage to short-term treatment despite evidence that eating disorder recovery often requires extended care. The eating disorder VA rating process required extensive documentation to demonstrate medical necessity for specialized treatment.

This financial reality affects treatment decisions in profound ways. I met numerous patients who left treatment prematurely due to insurance limitations rather than clinical readiness. Others avoided higher levels of care even when medically appropriate due to financial concerns.

For those without insurance or facing coverage limitations, options narrow dramatically. Some treatment centers offer scholarships or sliding scale fees, but demand far exceeds availability. Community support groups and public mental health services provide partial support but rarely the specialized care eating disorders require.

This systemic challenge remains one of the most significant barriers to recovery for many patients. Advocacy organizations continue pushing for insurance parity and expanded coverage, but progress remains inconsistent across different states and insurance providers.

Bloating ED Recovery: The Physical Challenges No One Discusses

The psychological aspects of eating disorder recovery receive significant attention, but the physical challenges are equally daunting and less frequently discussed. Bloating ED recovery emerged as one of the most difficult aspects of my healing process.

After years of restriction and purging, my digestive system responded to regular nutrition with extreme discomfort. Bloating, gas, constipation, and generalized abdominal pain became daily experiences during refeeding and early recovery.

“Your digestive system has essentially been hibernating,” my dietitian explained during a particularly difficult period. “It needs time to remember how to process regular meals.”

This physical discomfort created a serious recovery challenge. The bloating and fullness triggered intense eating disorder thoughts and urges to return to restrictive behaviors. Body image distress intensified as normal digestive processes created temporary physical changes that my disorder interpreted as permanent weight gain.

Practical strategies helped navigate this difficult phase:

- Smaller, more frequent meals to reduce digestive burden

- Gentle movement like walking after meals

- Avoiding carbonated beverages and gas-producing foods during the most sensitive recovery phases

- Wearing comfortable clothing that didn’t constrict my abdomen

- Utilizing distraction techniques during periods of maximum discomfort

The dietitian assured me that this phase would pass as my body healed, but the timeline varied significantly between individuals. For me, noticeable improvement took nearly six months of consistent nutrition—a discouraging timeframe when facing daily discomfort.

This aspect of recovery rarely appears in public discussions of eating disorders but represents a significant challenge for many patients. Better preparation for these physical realities might help patients persevere through this difficult but temporary phase.

Overeaters Anonymous Weight Loss: Exploring Support Groups

Professional treatment formed the foundation of my recovery, but peer support provided crucial supplemental help. I explored various support groups, including Overeaters Anonymous weight loss meetings, with mixed experiences.

The 12-step model offered valuable community and structure, particularly during transition periods between treatment levels. Meeting others in various recovery stages provided hope and practical strategies for navigating daily challenges.

However, aspects of certain groups proved problematic for my particular recovery needs. Some Overeaters Anonymous weight loss discussions contained language around “abstinence” from certain foods—a concept that reinforced my eating disorder’s black-and-white thinking rather than challenging it. The focus on weight loss in some meetings directly contradicted my treatment team’s emphasis on weight neutrality during recovery.

My dietitian helped me evaluate support group options more critically, identifying which aspects supported recovery versus potentially triggering eating disorder thinking. Eventually, I found a meeting specifically for eating disorder recovery that emphasized Health at Every Size principles rather than weight management.

This experience taught me that even well-intentioned support can sometimes work against clinical treatment goals. Recovery requires careful evaluation of all influences, including support groups, to ensure alignment with individual recovery needs.

Forget to Eat: When Recovery Creates New Challenges

One unexpected development in my recovery journey was the emergence of new eating-related challenges I hadn’t experienced during active illness. After years of constant food preoccupation, I began to occasionally forget to eat—a phenomenon that confused and concerned me.

“I spent years obsessed with food,” I told my therapist. “Now sometimes I forget to eat entirely. How is that possible?”

She explained that this pattern is actually common in recovery. “Your brain has been hyper-focused on food due to restriction and eating disorder thoughts. As those obsessive thoughts quiet down, food sometimes moves too far in the opposite direction, becoming an afterthought.”

This tendency to forget to eat created new recovery risks. Missed or delayed meals could trigger physical hunger that felt emotionally overwhelming after years of suppressing appetite. This intense hunger sometimes led to reactive eating that my disorder then labeled as “binging,” potentially triggering restriction or compensation.

The solution wasn’t returning to food obsession but developing structured external reminders until more normalized eating patterns could develop:

- Setting meal and snack alarms on my phone

- Using a simple meal plan framework to ensure consistent nutrition

- Creating environmental cues like prepping meals ahead

- Building eating into existing daily routines and habits

This phase highlighted how recovery isn’t simply about stopping eating disorder behaviors but developing a completely new relationship with food—one balanced between obsession and neglect.

Mia Eating vs. Recovery Eating: Language and Identity

Language profoundly shaped my experience of both illness and recovery. The term “mia eating” (referring to behaviors associated with bulimia) proliferated in online spaces I frequented during my illness, creating a coded language that normalized destructive behaviors.

In treatment, providers introduced alternative language that framed eating as nourishment rather than a moral or control issue. This linguistic shift gradually influenced my thinking, helping separate my identity from the disorder.

“You are not your eating disorder,” became a frequent reminder from my treatment team. “The part of you that engages in these behaviors is not the whole of who you are.”

This distinction between self and disorder proved crucial for recovery progress. Rather than seeing myself as fundamentally flawed or broken, I could recognize the eating disorder as a maladaptive coping mechanism that had developed for understandable reasons but now caused more harm than good.

Recovery involved creating a new identity beyond the eating disorder—rediscovering interests, relationships, and values that had been overshadowed by years of illness. This identity expansion didn’t happen automatically when behavioral symptoms improved; it required deliberate exploration and development.

Journaling helped track this evolution, providing evidence of growth when eating disorder thoughts tried to deny progress. Looking back at earlier entries revealed how completely the disorder had once dominated my thinking compared to the more balanced perspective gradually emerging.

Recovery Is Possible But Rarely Linear

Ten years from my first treatment admission, my relationship with recovery remains complex. I don’t experience active eating disorder behaviors, but certain thought patterns still emerge during stress. Physical health consequences from years of malnutrition require ongoing medical management. Hypervigilance around food and body image surfaces occasionally, particularly during major life transitions.

Is this recovery? By most clinical definitions, yes. By the perfectionistic standards I once held, perhaps not. The reality exists somewhere in between—significant healing with residual effects that require ongoing awareness and care.

What I know with certainty is that recovery, however imperfect, offers a quality of life incomparably better than active illness. Relationships, career opportunities, intellectual pursuits, and simple daily pleasures have returned to the center of my life. Food decisions occupy an appropriate amount of mental space rather than consuming all available bandwidth.

For those still struggling, please know that reclaiming your life from an eating disorder is possible. The path isn’t linear or perfect. Recovery looks different for everyone based on individual circumstances, resources, and needs. But step by imperfect step, meal by challenging meal, a different life becomes possible.

This article reflects personal experience and is not intended as medical advice. If you’re struggling with disordered eating, please reach out to qualified healthcare providers for appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

READY TO BLAST AWAY STUBBORN BELLY FAT QUICKLY? 🔥 Here’s your game-changer! Add this flavorless powder to your morning coffee and witness the incredible results! 💪

Leave a comment